Environmental Racism Toolkit

The purpose of this toolkit is to provide the reader with a better understanding of environmental racism, its history, how it plays out in so called Canada, and what you can do to take action. We have provided links and resources throughout this toolkit that can be of use to help the reader better identify environmental racism today and current roots of advocacy.

What is Environmental Racism?

Environmental racism describes the ways decision-makers perpetuate inequity and uphold systemic racism when making decisions on laws, policies, funding, city plans, and development. These decisions disproportionately impact the lives and health of Indigenous and racialized people in their community and the lands they occupy 1.

Environmental racism goes unnoticed because effected communities often lack the political and organizational power to call out industrial polluters and decision makers. Negative environmental impacts experienced by racialized communities are often viewed with skepticism and inequities are rarely monitored, requiring communities to provide evidence that there is a problem in the first place, or worse yet, having to wait until the adverse impacts begin spreading to other communities. This contributes to slow and inadequate access to relief.

Environmental racism can be defined as “the deliberate or intentional siting of hazardous waste sites, landfills, incinerators, and polluting industries in communities inhabited by minorities and/or the poor” 2. These designated sites called “Sacrifice zones” are considered spaces of Land that are “locally unwanted” and deemed appropriate for unwanted toxins.

Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor - Rob Nixon

The violence wrought by climate change, toxic drift, deforestation, oil spills, and the environmental aftermath of war takes place gradually and often invisibly. Using the innovative concept of “slow violence” to describe these threats, Rob Nixon focuses on the inattention we have paid to the attritional lethality of many environmental crises, in contrast with the sensational, spectacle-driven messaging that impels public activism today. Slow violence, because it is so readily ignored by a hard-charging capitalism, exacerbates the vulnerability of ecosystems and of people who are poor, disempowered, and often involuntarily displaced, while fueling social conflicts that arise from desperation as life-sustaining conditions erode.

A History Lesson on Environmental Racism and

the Environmental Justice Movement

The term environmental racism, originally coined by Dr. Benjamin Chavis, first emerged in the 1980s in North Carolina on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement of the 60s and Environmental Movement of the 70s 3. It originally came in response to the placement of a toxic chemical landfill in Warren County North Carolina, a predominantly Black community. This event led to a month-long protest, gaining widespread notoriety which sparked similar protests across the US and grew into the movement we know today.

Video: A Brief History of Environmental Justice

From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement - Luke W. Cole & Sheila R. Foster

When Bill Clinton signed an Executive Order on Environmental Justice in 1994, the phenomenon of environmental racism—the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards, particularly toxic waste dumps and polluting factories, on people of color and low-income communities—gained unprecedented recognition. Behind that momentous signature, however, lies a remarkable tale of grassroots activism and political mobilization. Today, thousands of activists in hundreds of locales are fighting for their children, their communities, their quality of life, and their health.

From the Ground Up critically examines one of the fastest growing social movements in the United States—the movement for environmental justice. Tracing the movement's roots, Luke Cole and Sheila Foster combine long-time activism with powerful storytelling to provide gripping case studies of communities across the US—towns like Kettleman City, California; Chester, Pennsylvania; and Dilkon, Arizona—and their struggles against corporate polluters. The authors use social, economic and legal analysis to reveal the historical and contemporary causes for environmental racism. Environmental justice struggles, they demonstrate, transform individuals, communities, institutions and the nation as a whole.

Access of this text can be found here:

Environmental Racism in so called Canada

Racism has been a part of Canada’s history since the early interactions of Europeans and Indigenous peoples. Land was seized from these communities and there was a clear lack of respect and lack of recognition of their rights to the land.

As we’ve discussed in the previous section, environmental racism is the development and implementation of environmental policy on issues such as toxic waste disposal sites, pollution, and urban decay in areas with a significant ethnic or racial population. Believe it or not, Canada is not immune to these policies. Black and Indigenous communities in Canada are exposed to environmental racism through exposure of toxic waste facilities, garbage dumps, and other sources of environmental pollution that negatively impacts quality of life and health 4

Video: Environmental Racism in Canada, Part 1

In the next few sections, we’ll dive a little deeper into specific case studies of environmental racism playing out across Turtle Island.

Shoal Lake 40

Shoal Lake 40 First Nation is a clear example of how environmental racism has played out in the making of Winnipeg. During the rapid expansion of the City of Winnipeg in 1890, it became clear that there was an urgent need to obtain clean drinking water to support the influx of settlers and industrial development in the city 5. In order to obtain permission to divert water from Shoal Lake into Winnipeg, the City required approval of the International Joint Commission (IJC), the Government of Canada, and the Province of Ontario. Nowhere did the city obtain permission or consideration of the residents of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation who would be severely impacted for the next hundred years. What ensued during this period was the displacement of residents of Shoal Lake 40 onto the lake’s peninsula that would later be severed with the construction of the aqueduct channel, landlocking the residents onto an artificial island 6. For the next century, Shoal Lake 40 residents were isolated without an access road or clean drinking water while Winnipeg reaped the benefits of the water they were taking.

Video: Vice News Shoal Lake 40

You can learn more about the history of the aqueduct and Shoal Lake 40 in Adele Perry’s book Aqueduct: Colonialism, Resources, and the Resources we Remember.

Aqueduct by Adele Perry

1919 is often recalled as the year of the Winnipeg General Strike, but it was also the year that water from Shoal Lake first flowed in Winnipeg taps. For the Anishinaabe community of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, construction of the Winnipeg Aqueduct led to a chain of difficult circumstances that culminated in their isolation on an artificial island where, for almost two decades, they have lacked access to clean drinking water.

In Aqueduct: Colonialism, Resources, and the Histories We Remember, Adele Perry analyses the development of Winnipeg's municipal water supply as an example of the history of settler colonialism. Drawing from a rich archive of historical sources, this timely book exposes the cultural, social, political, and legal mechanisms that allowed the rapidly growing city of Winnipeg to obtain its water supply by dispossessing an Indigenous people of their land, and ultimately depriving them of the very commodity--clean drinking water--that the city secured for itself.

Africville, Nova Scotia

Following the American Revolution, there was a significant migration of Black settlers entering Canada with many settling in Nova Scotia where they were promised freedom and land. Upon arrival, they were met with racism and prejudice from white settlers and were subsequently pushed to the outskirts of Halifax 7. Over time, the community grew into a tightknit, cultural hub that would formally be known as “Africville”. Although the residents found refuge from the anti-Black racism in the city’s center, they were not free from the daily injustices they faced from systemic anti-Black racism that ran the city’s operations. Residents of Africville paid taxes to the City of Halifax and yet they were cut off from any Municipal services such as sewage systems, clean drinking water, paved roads, garbage collection, public transportation and recreational spaces 8. Despite these barriers to an equitable livelihood, residents nurtured and supported each other and remained in Africville until 1965 when the City of Halifax began its “Urban Renewal Project” and Africville was ultimately destroyed 9. Leading up to this project, the city envisioned Africville as a site for Industrial development and in 1947 rezoned it as such 10. This led to the forced displacement and relocation of residents, which was strongly opposed. The “superior housing” that they were promised in exchange for the demolition of their homes did not materialize, leaving many residents unable to afford short term rentals and were ultimately forced to leave the city all together.

Video: Africville: The Black community bulldozed by the city of Halifax

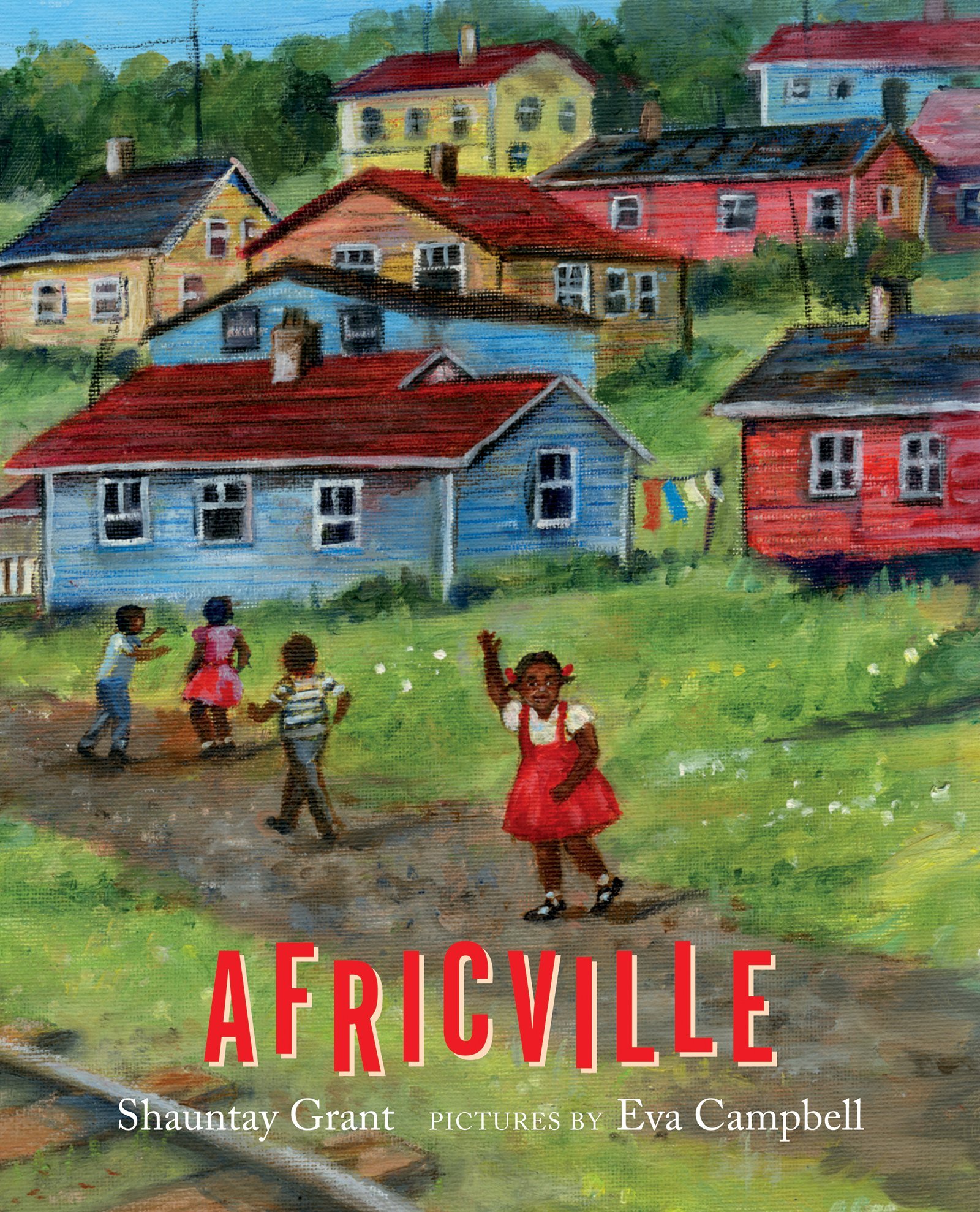

You can read more about the story of Africville in Shaunty Grant’s book Africville

Africville by Shaunty Grant

When a young girl visits the site of Africville, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the stories she’s heard from her family come to mind. She imagines what the community was once like —the brightly painted houses nestled into the hillside, the field where boys played football, the pond where all the kids went rafting, the bountiful fishing, the huge bonfires. Coming out of her reverie, she visits the present-day park and the sundial where her great- grandmother’s name is carved in stone, and celebrates a summer day at the annual Africville Reunion/Festival.

Africville was a vibrant Black community for more than 150 years. But even though its residents paid municipal taxes, they lived without running water, sewers, paved roads and police, fire-truck and ambulance services. Over time, the city located a slaughterhouse, a hospital for infectious disease, and even the city garbage dump nearby. In the 1960s, city officials decided to demolish the community, moving people out in city dump trucks and relocating them in public housing.

Today, Africville has been replaced by a park, where former residents and their families gather each summer to remember their community.

Grassy Narrows

With permission from the government of Ontario, the Dryden Chemicals Ltd dumped mercury into the English-Wabigoon River from 1962 to 1970. People from Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum Anishinabek (Grassy Narrows First Nation) who lived just upstream began to suffer the effects of severe mercury poisoning in fish , including damaged nervous systems, death, and multigenerational birth defects 11. The Province of Ontario issued the termination of the commercial fishery due to the imposed health risk of the contaminated fish. This led to mass unemployment of community members of Grassy Narrows who not only relied on the fish as their primary food source but also their main source of income. Dryden Chemicals Ltd officially shut down in 1976 but the harmful health effects of their actions have persisted to this day. Community members were forced to advocate for decades before the federal and provincial governments would begin to provide any form of aid or clean-up efforts. It was only in 2017 that the federal government began their clean-up of the English-Wabigoon River 12, and now in 2023 with the expected opening of a care facility dedicated to victims of mercury poisoning13, all occurring 50+ years after community members were poisoned.

Video: The Story of Grassy Narrows

You can read more about Grassy Narrows and its harmful lingering impacts in George Hutchison & Dick Wallace’s book Grassy Narrows.

Grassy Narrows

by George Hutchison and Dick Wallace

Documenting with sensitivity the tragedy of of mercury poisoning in the English-Wabigoon river system, in the traditional territory of Ojibway communities in Northern Ontario. “Grassy Narrows is a book that causes a quiet explosion of outrage in the heart.”

Chemical Valley

“Chemical Valley” is a 25km2 area of land between Ontario and Michigan that holds 40 percent of Canada’s polluting chemical companies 14. Chemical valley is located next to Aamjiwaang First Nation and the city of Sarnia, and in 2011 was deemed the worst air in all of Canada by the World Health Organization 15. The varied range of pollutants entering and mixing in the air of Chemical Valley creates a lethal concoction and has been linked to higher rates of cancers, respiratory illnesses, and reproductive health issues of the residents and victims of Chemical Valley 16. You can read more about the perceptions and coping strategies of the Aamjiwaang First Nation in Smith and Lockridge's study “Surrounded by Chemical Valley and “Living in a Bubble”: the case of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, Ontario” (2010), which provides in-depth interviews from community members affected 17.

Video: Canada's Toxic Chemical Valley (Full Length)

You can access this article to read more Here.

Wet’suwet’en First Nation

In British Columbia, TC Energy has been pushing to construct the infamous Coastal Gaslink Pipeline that would cross under Wedzin Kwa (Moris River) despite opposition from Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs 18. Wedzin Kwa is a sacred site and drilling under this river is not permitted in the territory. Undeterred by the hereditary chiefs' sovereignty over the unceded lands, TC Energy has continued its assault on the lands and its defenders. This has led to numerous demonstrations, blockades and protests across Turtle Island in support of the land defenders and hereditary chiefs of Wet’suwet’en 19.

This protest is ongoing. You can stay up to date with the land defenders by following their social media pages listed below.

Facebook: Gidimt’en Checkpoint

Instagram: @yintah_access

Twitter: @gidimten

Hollow Water First Nation

On May 16th 2019, the Provincial government of Manitoba approved the environmental license for Canadian Premium Sand’s (CPS) proposed silica sand extraction project “Wanipigow Sand” 20. The project site is located on the territory of Hollow Water First Nation, 160 kilometers northeast of Winnipeg, Manitoba. The project was widely opposed by residents of Hollow Water who set up Camp Morning Star to halt construction 21. The primary concerns over this project are the adverse impacts to air quality, ground water, noise pollution and its impacts on wildlife, hunting rights, and overall degradation to the land 22.

You can keep up to date with the land defenders on the ground at Camp Morning Star through their social media pages:

Facebook: Camp Morning Star

Instagram: @campmorningstar

Video: Camp Morning Star, Lake Winnipeg Project

Manitoba Hydro in Northern Manitoba

Manitoba Hydro is the leading provider of electricity in the province with six mega dams constructed over the Nelson River 23. Although hydroelectricity has been marketed as a green energy, there are detrimental impacts to the environment, local economies, human health, and social well-being of the Indigenous peoples obstructing the path to resource extraction. Mega dams operate through the development of artificial reservoirs which have flooded thousands of square kilometers of land in northern Manitoba 24. The observed effects from this flooding and development include spikes in mercury levels in the surrounding bodies of water, increased methane emissions from decomposing vegetation submerged during flooding, increased erosion of shorelines due to artificial fluctuations of water levels, terrestrial and aquatic habitat loss, and the gradual change of community structure due to these changes of the land.

Take a deeper look into the impacts of Manitoba Hydro in the North through the work available at Wa Ni Ska Tan

Video: Manitoba Hydro is Water Drunk

How to Take Action

Environmental racism, its past and ongoing impacts will not be resolved overnight. This will take ongoing work to dismantle and repair past wrong-doings.

You can take action by:

Further educate yourself on the topic and share this toolkit widely.

Stay up to date on our website: https://www.lwic.org/calls-to-action, where we will provide updates and actionable steps to take regarding addressing environmental racism at the micro and macro levels.

You can also read more about similar campaigns to address Environmental Racism here: https://www.enrichproject.org/resources/

Support Bill C-226

Three private member’s bills have been introduced since 2015, all with the intention of creating a federal strategy to address environmental racism. While the first two expired due to slow progress in house of commons, the third bill is now in the process. Along with partners in the Canadian Coalition for Environmental and Climate Justice, we are urging the federal government to expedite the passage of Bill C-226 25, An Act respecting the development of a national strategy to assess, prevent and address environmental racism and to advance environmental justice,

The strategy must include measures to:

Examine the link between race, socio-economic status, and environmental risk.

Collect information and statistics relating to the location of environmental hazards.

Collect information and statistics relating to negative health outcomes in communities that have been affected by environmental racism.

Assess the administration and enforcement of environmental laws in each province and

Address environmental racism including in relation to:

possible amendments to federal laws, policies, and programs.

the involvement of community groups in environmental policymaking.

compensation for individuals or communities.

ongoing funding for affected communities and

access of affected communities to clean air and water.

There is one simple way that you can encourage cross-party support for Bill C-226 and encourage all political parties to consent to the fast tracking of this bill through Parliament: Send an email or letter (template below) to MPs across the country to indicate why you support Bill C-226 and why Canada needs environmental racism legislation. It is especially important to reach out to Conservative MPs across the country since the Conservative Party was the only party that declined to support Bill C-230 at second reading and at amendments in 2021. Finally, share your thoughts with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Minister of Environment and Climate Change Steven Guilbeault about why Canada needs environmental justice legislation now.

References

1 MacDonald, E. (2020, September 20). Environmental racism in canada: What is it? what are the impacts, and what can we do about it?. Ecojustice. https://ecojustice.ca/environmental-racism-in-canada/

2 It matters where you live: Examples of environmental injustice in Canada. (n.d.). Environmental Justice. https://enviroinjustice.weebly.com/index.html

3 African American Voices in Congress. (n.d.). Environmental justice: History. http://www.avoiceonline.org/environmental/history.html#:~:text=The%20term%20%E2%80%9Cenvironmental%20racism%E2%80%9D%20grew,in%20Warren%20County%2C%20North%20Carolina.

4 Canadian Labour Congress. (2019, February 6). Ending discrimination: Why canada’s unions are highlighting environmental racism during black history month. https://canadianlabour.ca/why-canadas-unions-are-highlighting-environmental-racism-during-black-history-month/

5 Ennis, D. A. (2013). Manitoba History: The pressure to act: The shoal lake aqueduct and the greater winnipeg water district. Manitoba Historical Society. http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/72/aqueduct.shtml

6 Shoal Lake #40. (n.d.). About Shoal Lake 40: History. https://www.sl40.ca/about.htm

7 McRae, M. (n.d.). The story of africville. Canadian Human Rights Museum. https://humanrights.ca/story/the-story-of-africville

8 Tattrie, J. (2014, January 27). Africville. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/africville

9 Waldron, I. (2020, December 14). Environmental racism in canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/environmental-racism-in-canada

10 Tattrie, J. (2014, January 27). Africville. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/africville

11 Waldron, I. (2020, December 14). Environmental racism in canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/environmental-racism-in-canada

12 Prokopchuk, M. (2017, November 17). Grassy narrows leadership pleased with cleanup funding but says help needed for survivors. CBC: Thunder Bay. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/grassy-narrows-mercury-home-calls-1.4404889

13 CBC News. (2021, July 26). Grassy narrows to get $68.9M from Ottawa for centre to care for people with mercury poisoning. CBC: Thunder Bay. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/grassy-narrows-mercury-care-facility-ottawa-funding-1.6117975

14 MacDonald, E., Rang, S. (2007). Exposing canada’s chemical chemical valley: An investigation of cumulative air pollution emissions in the sarnia, ontario area. Ecojustice. 5-25. https://ecojustice.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/2007-Exposing-Canadas-Chemial-Valley.pdf

15 Kramer, D. et al. (2015). From awareness to action: The community of sarnia mobilizes to protect its workers from occupational disease. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy. 25(3), 377-410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048291115604427

16 Waldron, I. (2020, December 14). Environmental racism in canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/environmental-racism-in-canada

17 Luginaah, I., Smith, K., & Lockridge, A. (2010). “Surrounded by Chemical Valley and “Living in a Bubble”: the case of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, Ontario”. In Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 53(3), 353–370. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09640561003613104

18 Simmons, M. (2021, October 14). Why Tensions are escalating on wet’suwet’en territory over the coastal gaslink pipeline. The Narwhal. https://thenarwhal.ca/wetsuweten-coastal-gaslink-explainer/

19 Unist’ot’en Camp (2020). Wet’suwet’en supporter toolkit 2020. Unist’ot’en: Heal the People, Heal the Land. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/grassy-narrows-mercury-care-facility-ottawa-funding-1.6117975

20 Mining Technology. (2019, December 19). Wanipigow sand project, manitoba. https://www.mining-technology.com/projects/wanipigow-sand-project-manitoba/

21 Mangeli, B. (2019, June 13). Camp morning star. Waniskatan. https://hydroimpacted.ca/camp-morning-star/

22 Wilt, J. (2019, September 16). ‘This is sacred’: The fight against a massive frac sand mine in manitoba. The Narwhal. https://thenarwhal.ca/this-is-sacred-the-fight-against-a-massive-frac-sand-mine-in-manitoba/

23 Elkaim, A. V. (2020, November, 7). State of erosion: The legacy of manitoba hydro. The Narwhal. https://thenarwhal.ca/state-of-erosion-the-legacy-of-manitoba-hydro/

24 Wa Ni Ska Tan. (n.d.). Impacts: Impacts of hydropower in manitoba. https://hydroimpacted.ca/impacts/

25 Bill C-226 https://www.parl.ca/legisinfo/en/bill/44-1/c-226